I was at Costco getting gas. The guy across from me had a tattoo that caught my eye—it was ancient Greek: ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ.

And suddenly, the meaning of a famous saying of Jesus became clear in my mind.

This kind of thing happens to me. It’s why I go to Costco. I interrupted the tattooed man: “Sir? Sir?” He turned with a mixture of curiosity and annoyance.

“I write about Greek—can I take a picture of your tattoo?”

His look changed into a smile—this is one he had not heard before. He raised his arm proudly. I snapped the picture above.

You’ve probably seen ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ before on a bumper sticker. Probably on a pickup truck featuring gun racks, if I may be permitted one stereotype. It’s an NRA-style rallying cry, one in fact echoed by Charlton Heston in his own famous update of the phrase.

The phrase comes from the words the Spartan king Leonidas used to respond to the invading Persian king Xerxes in 480 B.C. Xerxes demanded that Leonidas surrender his weapons, and Leonidas replied, “Come and take them.”

Certain expository preachers

But if certain of my fellow expository preachers got hold of this phrase, they would hasten to “clarify” it, like so:

The first word is a participle, so literally what Leonidas said was, “Coming . . . ,” or “Having come, take.”

That is all true. You’re right, certain expository preachers. Wikipedia’s article on this famous phrase says the same thing, and it sounds exactly like some commentaries I’ve read and not a few sermons I’ve heard. Here’s Wikipedia:

The first word, μολών molōn (“having come”) is the aorist active participle (masculine, nominative, singular) of the Greek verb βλώσκω blōskō “to come.” The aorist stem is μολ- (the present stem in βλώ- being a regular contraction of μλώ-, from a verbal root reconstructed as melə-, mlō- “to appear”). The aorist participle is used in cases where an action has been completed, also called the perfective aspect. This is a nuance indicating that the first action (the coming) must precede the second (the taking).

Go and make

This is where the saying of Jesus comes in. You see, when Jesus says, “Go . . . and make disciples of all nations” (Matt 28:19), he uses a similar construction: aorist participle + imperative finite verb (πορευθέντες οὖν μαθητεύσατε).

Now, dear expository preachers, I love you and I am one of you. But this kind of thing is your linguistic downfall, your homiletical siren song, your exegesis-enhancing steroid that has been banned by OLSHA.

Because this is what you want to say—I know you! You want to say, “Jesus uses a Greek participle here which, literally, means ‘Having gone.’ This means he assumes his hearers are going out to spread the gospel! It’s like the going is assumed, and once you’ve gone, then you need to make disciples.”

But that’s where ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ helps us. Because it’s not Bible, we’re less inclined to read extra meaning into it, meaning that goes underneath and beyond the English translation in our hands. ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ means—it has to mean, given the context—only one thing: “COME AND TAKE THEM.” There’s just no way that Leonidas, in that moment when he is called upon to be the macho trash talker insolently defying the massive opposing army, said something as frilly and hair-splitting as, “Dear Xerxes, once you have come, take.”

ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ provides some evidence that participle + imperative was just the ancient Greek way of saying stuff. Good idiomatic Greek that sounds like the Greek of native speakers often went participle + imperative in situations in which good idiomatic English that sounds like the English of native speakers would never, ever do this. “Having come, take” is not an accurate translation of ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ. It belongs buried deep in the niceties of a grammar book that no self-respecting Spartan warrior would ever touch (because he uses it in Λογος, of course).

Jesus, then, did not say, “Having gone, make disciples.” He said, “Go and make disciples.”

Using Logos to study a Greek construction

Now I have to acknowledge that Leonidas would have written his famous words five centuries before Christ (though they are reported to us by Plutarch in the first century) and that the word for “come” that he uses (βλώσκω, blosko) does not appear in the NT. Liddel-Scott-Jones suggests that it dropped out of the language around the time of the Septuagint (in which it also does not appear). Similarly, what counted as good idiomatic Greek surely changed between the death of Leonidas and the birth of Jesus. But I observe the same participle + imperative pattern in the New Testament.

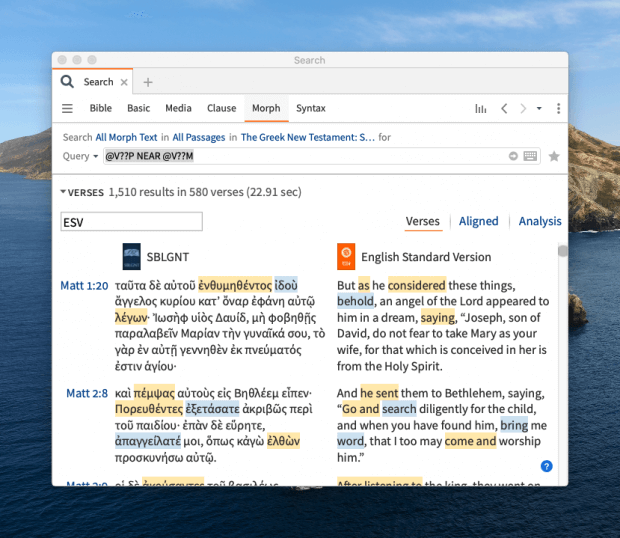

Using the Morph search tab in Logos Bible Software, I looked for places where imperatives follow participles. I cast a wide net by looking for any time one appeared “NEAR” the other:

The second hit I got is similar to Jesus’ wording in the Great Commission. It’s Herod sending the wise men to look for baby Jesus. And it’s participle + imperative.

Πορευθέντες ἐξετάσατε ἀκριβῶς περὶ τοῦ παιδίου.

Go and search diligently for the child. (Matt 2:8)

Here’s another from 12 verses later, and it uses the same root as ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ:

Ἐγερθεὶς παράλαβε τὸ παιδίον καὶ τὴν μητέρα αὐτοῦ.

Rise, take the child and his mother. (Matt 2:20)

English speakers would just never say in these contexts, “Going, search for the child,” or “Rising, take the child.” It would be like saying to my kids—and this one was suggested by my wife, who got better grades in Greek than I did—“Sitting down, eat your dinner!”

It is right for translators to do in these places what they nearly always do and “change” the participles into English imperatives. They aren’t being overly interpretive; they are doing their job. They are translating from Greek into English. “Rising, take the child” isn’t English, because no one would ever say that. It’s Biblish, a linguistic surd, zombie syllables. And Tyndale didn’t die to give us Biblish, because it goes by a more common name: gibberish.

When expository preachers make a point of saying, “What-x-passage-really-means-is . . . ,” and they then give their hearers Biblish, they are erecting a linguistic barrier to understanding that is unnecessary at best and misleading at worst. Paul in 1 Corinthians 14 says that edification requires intelligibility; he even expects “outsiders or unbelievers” (14:23 ESV) to be able to basically understand what they hear in church. Almost every time I hear, “In the Greek, this literally means . . .” I cringe.

Now, there are places where the context indicates that the Greek idiom of participle + imperative shouldn’t be rendered as two imperatives in English. Here’s one:

σὺ δὲ νηστεύων ἄλειψαί σου τὴν κεφαλὴν.

When you fast, wash your head. (Matt 6:17)

In this case, context shows that the best translation into English would not involve turning both these verbs into imperatives. So I’m not setting up a new grammar rule in which participle + imperative in NT Greek must always become imperative + imperative in English. I’m trying, in my small way—for the eternal honor of King Leonidas and of some guy at Costco—to restore context to its rightful rule over grammar.

A practical suggestion here: before you take a grammar book’s word for something, and before you go repeating a footnote in a commentary, use Logos to check up on their work. Check newer commentaries that might interact with the claim. (After writing this piece I checked a few, and Carson says the same thing I do—but includes no pictures of tattoos). But go the extra mile: look at similar constructions and see if their conclusions work elsewhere. If they do, the writers you’ve read are probably describing something that is really happening in the language. If not, they’re finding more meaning than God put there, a common temptation for certain expository preachers . . .

A public threat

I need to end with a public threat. If someone says to me, “Surrender your linguistic observations from daily life that shed light on NT interpretation; there are too many of them!” If someone says that, I will beat my chest and say, ΜΟΛΩΝ ΛΑΒΕ***