I was recently dispatched to Melbourne to visit Frank Andersen and Dean Forbes. One of the things I was assigned to discover — other than what kangaroo chili tastes like* — was the underlying linguistic/textual/grammatical philosophy of the Andersen-Forbes database (hereafter, A-F). Sure, they’ve marked the entire Hebrew Bible for syntax, but what exactly does that mean?

What I found out is that Frank and Dean are hard to pigeon-hole. Dr. Andersen claimed that they are committed iteratists, by which they mean that they proceed one iteration at a time, constantly improving their data, constantly allowing their approach and their data to evolve. Furthermore, Frank and Dean are empiricists, at least to the extent that they will insist that every proposition and assertion about the Hebrew language of the Bible be rigorously tested with observable and quantifiable data to see if it indeed be true. On the other hand, Frank calls their approach eclectic because they have drawn from the insights and approaches of various schools of thought along the way, and will continue to do so.

That is not to say that their work recognizes no system, only that it is a system unto itself: descriptive rather than prescriptive, and complex rather than reductionist. For this reason, the A-F syntax markup has more categories rather than fewer.

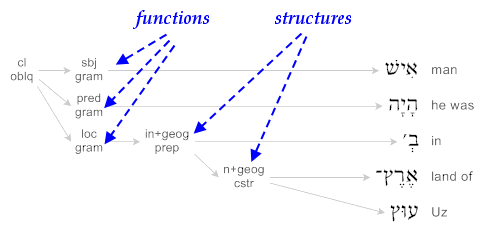

When we look at an A-F graph, what we are seeing are structures that fulfill functions. (Structures fulfill functions. Remember that, its going to be on the final.)

Graphs and Labels and Arrows, Oh My!

The A-F syntax database is best represented by a collection of graphs (see my previous posts here and here), which in A-F are called phrase markers.

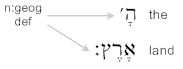

The phrase marker labels have two parts, one on each line: the first line is a descriptive label of the structure, and the second is the licensing relation, that is, the grounds upon which the structure is formed. The phrase-marker label n:geog describes the nature of the phrase (a noun phrase of geography); the structure itself is licensed by the fact that the definite article precedes the noun, def.

The Seven Levels of Syntax

The A-F database marks seven layers of syntax information, which from the smallest to the largest are:

- text segments, the individual words of the Hebrew Bible;

- tight phrases, like definite noun phrases (the land) or tight coordinations like hendiadys (male and female, husband and wife);

- simple phrases, that is, noun phrases or prepositional phrases that do not (directly) involve complex unions or juxtapositions;

- compound phrases, or phrases made up of other phrases (the cities of Judah and around Jerusalem);

- clause immediate constituents, the functional units of a clause;

- clauses, which are the units of a single predication;

- supra-clausal structures, those units of syntax that exist above the clause, also known as discourse units.

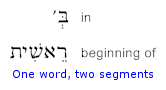

Text Segments

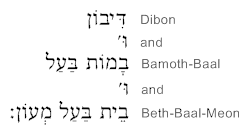

The smallest unit of analysis in the Andersen-Forbes database is the text segment. Crudely, these can be thought of as the individual words of the Hebrew Bible. However, these units are not always the same as the graphical words you might see in a printed text, that is, they are not always sequences of letters separated by white space or punctuation marks; rather, they are the smallest units of meaning that were deemed useful for analysis.

Many text segments are single graphical words.

Text segments may also consist of multiple graphical words. In Joshua 13:17, the place name Bamoth-Baal is two graphical words, and Beth-Baal-Meon is three; each name gets a single segment in the analysis:

Tight Phrases

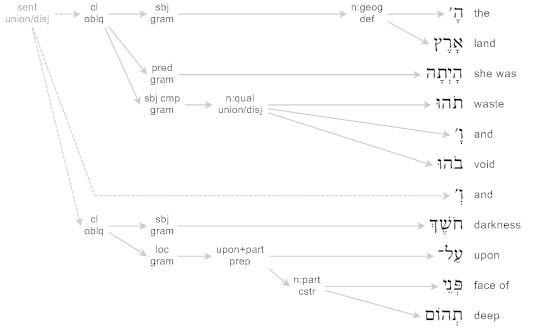

This terminology is unique to Andersen-Forbes as far as I know, but it’s pretty straightforward: Tight phrases are simple phrases that are bound together especially tightly. A noun and its definite article is an example of a tight phrase. Examples of hendiadys, where two terms are joined together with and such that they make a single syntactic unit, are also tight phrases (without form and void in Genesis 1:2).

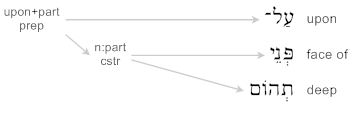

Simple Phrases

Simple phrases are of two types: prepositional phrases and several subclasses of noun phrases. In Genesis 1:2, upon the face of the deep is a simple noun phrase (the face of the deep) contained within a simple prepositional phrase (in …):

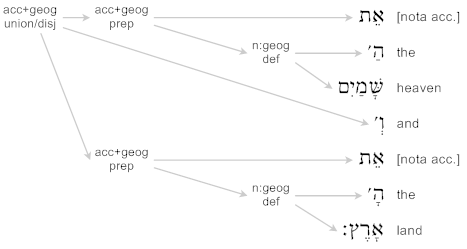

Compound Phrases

Compound phrases are made by joining simple phrases, tight phrases, or segments together. In Genesis 1:1, the heavens and the earth is a compound phrase that is made from two simple phrases:

Clause Immediate Constituents

Up to this point, all of the syntax categories have been labeling the form that the syntactic structures take: Are they simple noun phrases or compound prepositional phrases? Are they one segment or many? These sorts of labels describe what the structures are, but they dont address what the structures do in the clause.

Remember from above, structures fulfill functions. That is just to say that sequences of words (ahem, text segments) come together within a text for some reason. The clause immediate constituent labels in the A-F database label the function that a structure fulfills within its clause. A single form may have many functions, depending on what it’s doing in the clause. For example, a simple noun phrase may fulfill the function of subject, or object, or location, or movement goal, or … you get the picture.

In short, if you want to examine clause-level functions, then you want to examine the clause immediate constituents.

In the graph above (from Job 1:1), we have a clause that consists of three functional constituents: first a subject (sbj), then a predicator (pred), and finally a location (loc). There was a man in the land of Uz. The function of each of those constituents is fulfilled by the three structures: man, a noun functioning as subject; he was, a verb functioning as predicator; and in land of Uz, a prepositional phrase functioning as a location.

Clauses & Clause-Like Structures

Clauses typically include a predicator (verb or verb-like thing) and the other clause immediate constituents that accompany it. (Of course, in biblical Hebrew, a subject plus some number of other constituents can make a clause with no predicator the verbless clause.)

Supra-Clausal Structures (Discourse)

The A-F syntax markup is complete up through the clause level. Frank and Dean are currently marking structures larger than individual clauses, such as sentences or discourse units, and the current database has fragments of their provisional, interim markup for those units. Because of their uncertain nature, these units are de-emphasized in the Libronix DLS graphs. They are grayed-out a little, and any lines leading to or from them are dashed:

* Kangaroo chili tastes like venison or elk chili its a red meat with a lot of flavor. Of course, in the chili I had it was finely ground and surrounded by a lot of other things, so I may just have to eat a kangaroo steak or two before I really close the book on this issue. I can confidently say that it didnt taste at all like rabbit, which was my initial expectation. (I mean, theyre just big rabbits, right? Shows what I know.) In any case, Frank Andersen makes a mean kangaroo chili. His minestrone aint half bad, either.