If you can’t use the Bible, you don’t really understand it.

It may sound backwards to speak of “using” the Bible: we don’t stand over the Bible, twisting it to our ends; the Bible stands over us and is one major means by which God uses us.

That’s all true, but think of it this way: when I’m tempted, or struggling, or arrogant, or lying, or spiritually lethargic, what am I supposed to do as a Christian? I’m supposed to avail myself of the grace of God, and one major means by which God gives me that grace is my Bible. If my mind is blank of Bible in times of trouble, I’m not using God’s word the way I’m supposed to. To apply a text of Scripture well is to use it with love and faith according to its intended purposes.

To seek the meaning of a Bible passage at all is precisely to seek to use it to meet some human need. Says theologian John Frame,

Every request for “meaning” is a request for an application because whenever we ask for the “meaning” of a passage we are expressing a lack in ourselves, an ignorance, an inability to use the passage. Asking for “meaning” is asking for an application of Scripture to a need; we are asking Scripture to remedy that lack, that ignorance, that inability. (83)

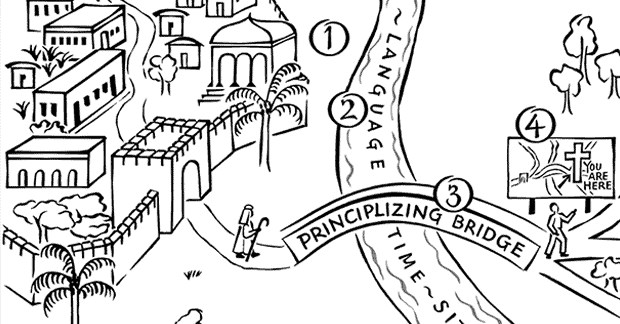

We’ve been seeking for the last few weeks to use the precious words of Psalm 44 according to their intended purposes. We first observed them in their ancient “town”—their historical-cultural context. Then we interpreted them by crossing the bridge between the ancient town and our modern one; we looked for theological principles in the text.

Now we get to bring Psalm 44 into our town, to use it for our needs today. Duvall and Hays suggest three steps for the application phase of your Bible study.

Observe how the principles in the text address the original situation

If you’ve been reading the series so far, this one’s easy. We’ve basically already done it. If you’re wondering how to do this with whatever psalm you’re studying, just go back to your notes from the interpretation stage of your study. What theological principles did you draw out? The principles in Psalm 44 are, or at least include,

- It’s okay to ask God why during times of terrible, undeserved (national) trial, if you ask in faith.

- It is for the Lord’s sake that such trials occur.

- Believers may appeal to God for help and relief based on his covenantal love.

An ancient Israelite in his “town” could pray Psalm 44 directly to the Lord—if indeed he had “not been false to the covenant” (v.17). Such a believer in Yahweh could pick up the strong hint in this psalm (v.22) that his trials are from and to the Lord and could draw comfort from that truth. And he could feel emboldened to pray, even and especially with his Jewish neighbors in public, that the Lord would remember his covenant and end the trial he’d sent to his people.

Do you see what I just did? It’s not complicated: I just took the principles I already uncovered and asked myself how they would be applied in the original context. This is the sort of thing you can and should do with any psalm you study.

Discover a parallel situation in a contemporary context

Duvall and Hays’s second step is more difficult. Does anyone reading this blog post have a situation truly parallel to that of Psalm 44? When the whole point of the psalm is the expression of a national lament by Israel, then what can Gentile nations do with the psalm—if we Gentiles are trying to use the psalm according to its intent?

I have never been a member of a nation that could say, “Why has this trouble come upon us even though we haven’t been false to your covenant?” I have been part of much smaller groups of people—churches, parachurch institutions—that could feasibly have prayed much of the psalm (keeping in mind that the covenant to which we appeal would be the New Covenant and not the Old). But, really, “for your sake we are killed all the day long”? It’s never been anywhere near that bad for any group of Christians I’ve been a part of. How can I use Psalm 44 faithfully if I can’t find a direct contemporary parallel situation?

I used to struggle often over this kind of question while reading the Psalms—until Mark Futato, in his Mobile Ed course on the Psalms, emboldened me to do two things that at first felt wrong but that I always found myself doing anyway: I (very carefully) individualize group statements in the Psalms; I even (very carefully) spiritualize some of the details. In this way I find a parallel situation.

Futato points out that “The language in the psalms themselves is typically quite general and, therefore, quite universal.” For example, “Throughout the book of Psalms there are references to the enemies, and we virtually never know with any specificity who the enemies are.”

There’s a certain timeless quality, there’s a certain generalized, universal nature to the language in the book of Psalms, and that presents an interpretive challenge. But when we flip that coin over, it actually turns out that that interpretive challenge is an interpretive blessing. There’s a blessing to the ambiguity that we find in the book of Psalms. The general and universal nature of the language in the psalms makes it all the easier to appropriate that language and apply it to contemporary situations: in the church, in the world, in our own lives. (§20)

Even if I am not a nation, nor even in a nation under violent attack, I do have enemies—spiritual enemies. The world, the flesh, and the devil. When I have been under attack from these enemies I have needed to appeal to God for relief. Nations and individuals can ask the very same question in times of violent trial: we didn’t deserve this, so where’s God? So I ask it (when indeed I didn’t deserve my trial), in the words of Psalm 44. I can’t see this as wrong, especially if we never forget that when we do this, we’re using the psalm in a way the original human author couldn’t have intended. But the divine Author of Psalm 44 placed those words there not just for the ancient town but for mine. It’s an expression of faithfulness to God, not unfaithfulness to authorial intent, to look for righteous ways to use this psalm today.

Make your applications specific

And here I will let you in on another hermeneutical (and homiletical) practice I have found helpful. If I personally am not in a situation parallel to that of a given psalm, I try to put myself in the shoes of someone who is. I ask, How could so-and-so use this psalm faithfully in so-and-so’s situation? I make the application very specific, just as Duvall and Hays direct.

An example jumped out at me just recently. I was reading a history of the prosperity gospel by Duke University professor Kate Bowler. This is a woman exactly my age, 35, who publicly (in the New York Times, no less) professes faith in Christ, has a promising academic career in front of her, and just found out that she has terminal stomach cancer.

Her article in the Times about her experience is profound, and so well written (I bought her book on the strength of the prose and insight). I urge you to read it.

When Bowler received her diagnosis, her friends rallied around her, and they did so with a very American belief in individual, can-do agency. What the agent is supposed to do depends, of course, on the god of the person doing the recommending:

One of the most endearing and saddest things about being sick is watching people’s attempts to make sense of your problem. . . . When did you start noticing pain? What exactly were the symptoms, again? Is it hereditary? I can out-know my cancer using the Mayo Clinic website. Buried in all their concern is the unspoken question: Do I have any control?

I can also hear it in all my hippie friends’ attempts to find the most healing kale salad for me. I can eat my way out of cancer. Or, if I were to follow my prosperity gospel friends’ advice, I can positively declare that it has no power over me and set myself free.

Kate Bowler finds herself in a situation parallel to that of the sons of Korah in Psalm 44: she is withering away at the prime of her life for no reason she can fathom:

The most I can say about why I have cancer, medically speaking, is that bodies are delicate and prone to error. As a Christian, I can say that the Kingdom of God is not yet fully here, and so we get sick and die.

Existential questions about God’s presence in and reasons for our cancers, our battles, must drive us to the same point to which they drove the psalmist. He set an example for us in which we must turn our difficult questions into petitions: “Redeem us for the sake of your steadfast love!”

Would Bowler be individualizing or spiritualizing Psalm 44 to use it this way?

When Paul quotes Psalm 44

If so, she’s in good company. When Paul uses Psalm 44’s most famous line (and it is the most famous because he used it) in Romans 8, he does so to echo and expand the slim answers Psalm 44 gives to the question of inexplicable suffering. It can’t be an accident that when faced with the insistent questions raised by real tribulation, Paul and Psalm 44 both give the same answer: the steadfast love of God.

Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or danger, or sword? As it is written,

‘For your sake we are being killed all the day long;

we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered.’No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Psalm 44 points in a way it’s author couldn’t have known to Jesus (1 Pet 1:10–12). The supreme example of divine steadfast love, and the reason we shouldn’t despair when our bellies cling to the dust, was when one Man was slaughtered like a sheep for our sakes.

The way to use Psalm 44 is the way Paul used it: find in it an affirmation of the universal theological principle, made Yes in Jesus, that God bears steadfast love for all members of his covenants.

***

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.