By Steve Runge

Often when we’re studying [a book] of the Bible, we come to a place where the author digresses from the big idea to make a side comment. To understand the passage, we have to figure out how to distinguish the main point from the digressions. In some passages that’s fairly easy, but in others it can be frustratingly difficult.

Digressions occur frequently in every kind of writing—not just in the Bible—and they come in everyday conversation, too. In English, we naturally mark the beginning and end of such digressions with adverbs like “so” or “now.” For example:

There was an accident at work and an old friend of mine was injured. Now he used to work in a different department, that’s where we met. So anyhow, he was trying to move something by himself when . . .

The big idea of this discourse is to tell you about the accident, not about where the friend used to work or how we met. The adverbs help signal the beginning and end of a digression. This information isn’t the main point, but it fills in some details that provide context.

In the biblical Greek text of the New Testament, this same kind of infilling can be accomplished through something called “continuative relative” pronouns. The name isn’t important; what’s important is the function of these grammatical markers. Just like adverbs in English, they signal that the writer (or speaker) is embedding a chunk of descriptive information within a bigger idea. In other words, certain terms in Greek help distinguish the main points from the digressions.

Unfortunately, these marker terms often get missed when the Greek is translated to English—not because the translators were inept, but simply because the two languages don’t work the same way.

This issue shows up a lot in the letters of Paul. He had a tendency for piling one thought on top of another, sometimes creating long, run-on sentences that span several verses. But to make these long sentences read better in English, translators usually break them up into shorter sentences. This can make it harder to distinguish Paul’s big idea from his side comments.

Even if we don’t know Greek, Logos Bible Software can help us recognize the digressions in a passage by turning the text into an outline. To see how this works, let’s look at an example from Philippians 2.

Seeing the shape of the text

The chapter begins with several exhortations. In Philippians 2:2, Paul tells the believers to “be like-minded,” and he elaborates on this idea in verses 3–4. In verse 5, he gives another main command—repeating the big idea to be like-minded from verse 2, but now linking it to the attitude that Christ Jesus exhibited. This is immediately followed by the “Christ hymn” in verses 6–11, where Paul celebrates Jesus’ humbling of himself.

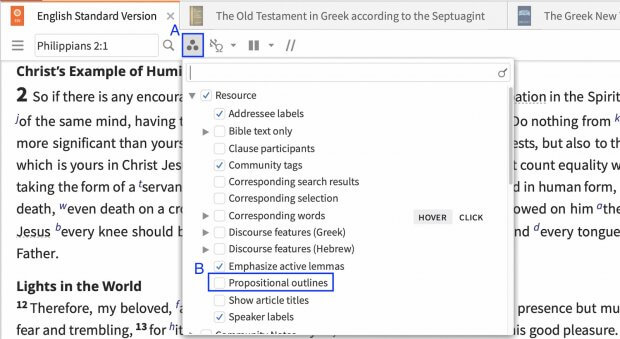

In Logos, a feature called propositional outlines can help us keep track of the big idea in Philippians 2:6–11. To turn on this visual filter, go to your preferred Bible version and open the Visual Filters menu. See [A] in the screenshot below. Then simply check the box for “propositional outlines.” [B]

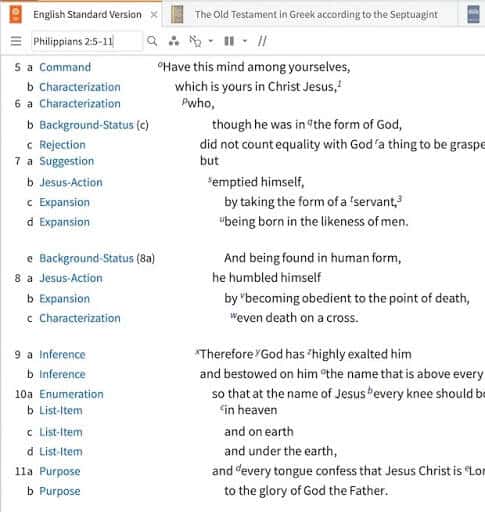

The propositional outlines filter uses indentations to represent grammatical dependency. In Philippians 2, you can see the indentation that begins at verse 6a and extends all the way through verse 11b:

Even when we’re reading in English, the propositional outline helps us see what’s going on in the Greek text. The entirety of verses 6–11 is set off by a continuative relative pronoun—the Greek word hos, meaning “which” or “who” (v. 6). This pronoun signals that, within Paul’s flow of thought, the beautiful “Christ hymn” is really a side comment! Paul is expanding on verses 2 and 5, illustrating what he envisions like-mindedness to look like.

Paul’s big idea in Philippians 2:6–11

Paul’s letters bear the linguistic characteristics of “hortatory discourse”—a fancy way of saying they’re more focused on changing behavior than teaching doctrine. The point of the doctrine is to change our thinking, to give us examples (and sometimes counterexamples) that would move us to action. That is precisely what we find here in Philippians 2.

Paul’s big idea in this passage is not to teach us about Jesus, but to foster like-mindedness among the Philippian believers. He illustrates this by using the “Christ hymn” to highlight how both the Son and the Father gave something up in order to put the other’s interests before their own.

Jesus gave up his position in heaven and even his human dignity to suffer and die on the cross in obedience to the Father’s plan to redeem humanity (vv. 6–8). In response, we see the Father bestowing on the Son the name that is above every name and having all creation bow the knee to the Son instead of ostensibly to the Father (vv. 9–11).

The passage certainly offers insights about Christ. But despite all the high Christology gleaned from 2:6–11, within the larger context, this hymn serves as motivation for Paul’s audience to set aside their own interests in order to achieve God’s intention for like-mindedness among believers.

This in no way diminishes the significance of these verses; it simply respects Paul’s unambiguous choice to embed these comments about Jesus within his big idea, found in the commands of verses 2 and 5.

In whom . . . in whom . . . in whom

For another good example, check out Ephesians 1. The Greek text has a single run-on sentence stretching from verse 3 all the way to verse 14. Paul begins by praising God the Father in verse 3: “Blessed is the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The focus on the Father continues through verse 6.

The shift to Jesus in verse 7 could create the impression that Paul’s discourse is now focused on the Son instead of the Father. But the propositional outline in Logos shows us the Greek is doing something different. The repetition of the phrase en hō (“in whom”) at the beginning of verses 7, 11, and 13 creates three parallel statements about Jesus that are supporing Paul’s big idea about the Father in verse 3.

Even if we don’t know Greek, the outline in Logos helps us see what’s going on in Paul’s flow of thought. He is praising God the Father as the source of all spiritual blessings in Christ.

***

This article was originally published in the January edition of Bible Study Magazine. Scripture quotations are the author’s translation.

Steven E. Runge is an academic editor at Lexham Press. He previously served as a scholar-in-residence at Faithlife, the maker of Logos Bible Software. His research focuses on the intersection of cognitive functional linguistics and Koine Greek exegesis.