It’s been called the “heart” of the promised land—a 141-square-mile triangle in the north-central area of Israel.

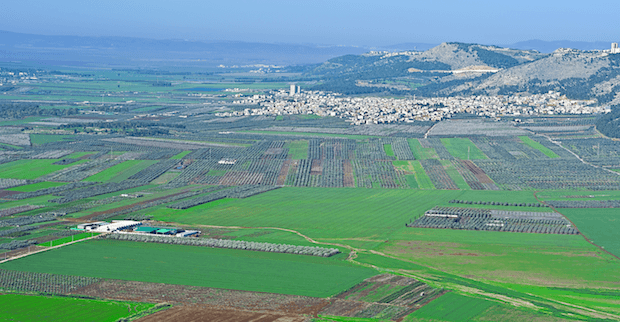

Today, the Jezreel Valley is Israel’s breadbasket. A beautiful plain of fertile fields and winding roads, it’s hemmed in by rolling mountains that offer stunning scenic views.

But its modern-day beauty hides a bloody and violent history.

What happened at the Valley of Jezreel?

Here Jezreel’s rulers killed Ahab’s 70 sons, put their heads in baskets, and brought them to Jehu (2 Kings 10:1–11). Queen Jezebel murdered Naboth in his own vineyard in Jezreel (1 Kings 21:1–23) and later died after being thrown from a palace and devoured by dogs. Pharaoh Neco killed King Josiah in the Jezreel Valley (2 Kings 23:30).

No less than thirty-four battles have occurred in or around this area.1

It was here that:

- Deborah and Barak trounced Sisera at the base of Mount Tabor at the eastern end of the valley (Judges 4–5)

- The Philistines attacked and defeated the Israelites on Mount Gilboa on the valley’s southeastern side (1 Sam 29:1; 31)

- Gideon defeated the Midianites, Amalekites, and their allies from the east just north of Mount Gilboa (Judges 6–7)

- The Crusaders fought four separate battles in the twelfth century

- Napoleon Bonaparte crushed the Ottomans in 1799

- General George Allenby fought the Ottoman army for control of the area in 1918

For millennia, it’s been like a magnet wooing the nations to war—and for good reason.

Keep reading to learn all about the significance of the Jezreel Valley, or jump to the topics below that interest you:

- Are there other names for the Jezreel Valley?

- Where is the Jezreel Valley located?

- What strategic importance did the Jezreel Valley have?

- What distinguishes the topography of the Jezreel Valley?

- What biblical cities are connected with the Jezreel Valley?

- Is the Jezreel Valley in prophecy?

Are there other names for the Jezreel Valley?

The Jezreel Valley is also known as Jezreel of Issachar, the Valley of Esdraelon, and the Valley of Armageddon.

Where is the Jezreel Valley located?

According to the Lexham Bible Dictionary:

The name Jezreel refers to both a valley and a city in that valley. The Jezreel Valley is located south of Galilee and north of the Hill Country of Ephraim. Greek sources refer to it as the Valley of Esdraelon. It is also popularly referred to as the Valley of Armageddon (Rev 16:16), though there is debate over the identification (see these articles: Armageddon; Megiddo). The valley extends about 25 miles in a northwest-southeast direction and is about 10 miles wide. The River Kishon drains the valley to the west. The Harod stream drains the eastern part of the valley, also known as the Harod Valley, before flowing into the Jordan River.

The valley floor is composed of alluvial soil that has been washed down from the surrounding hills and is very fertile. A basalt flow extends across the valley from the vicinity of Mount Tabor toward Megiddo. This basalt ribbon provides a solid foundation for the highway that has crossed the valley since ancient times.

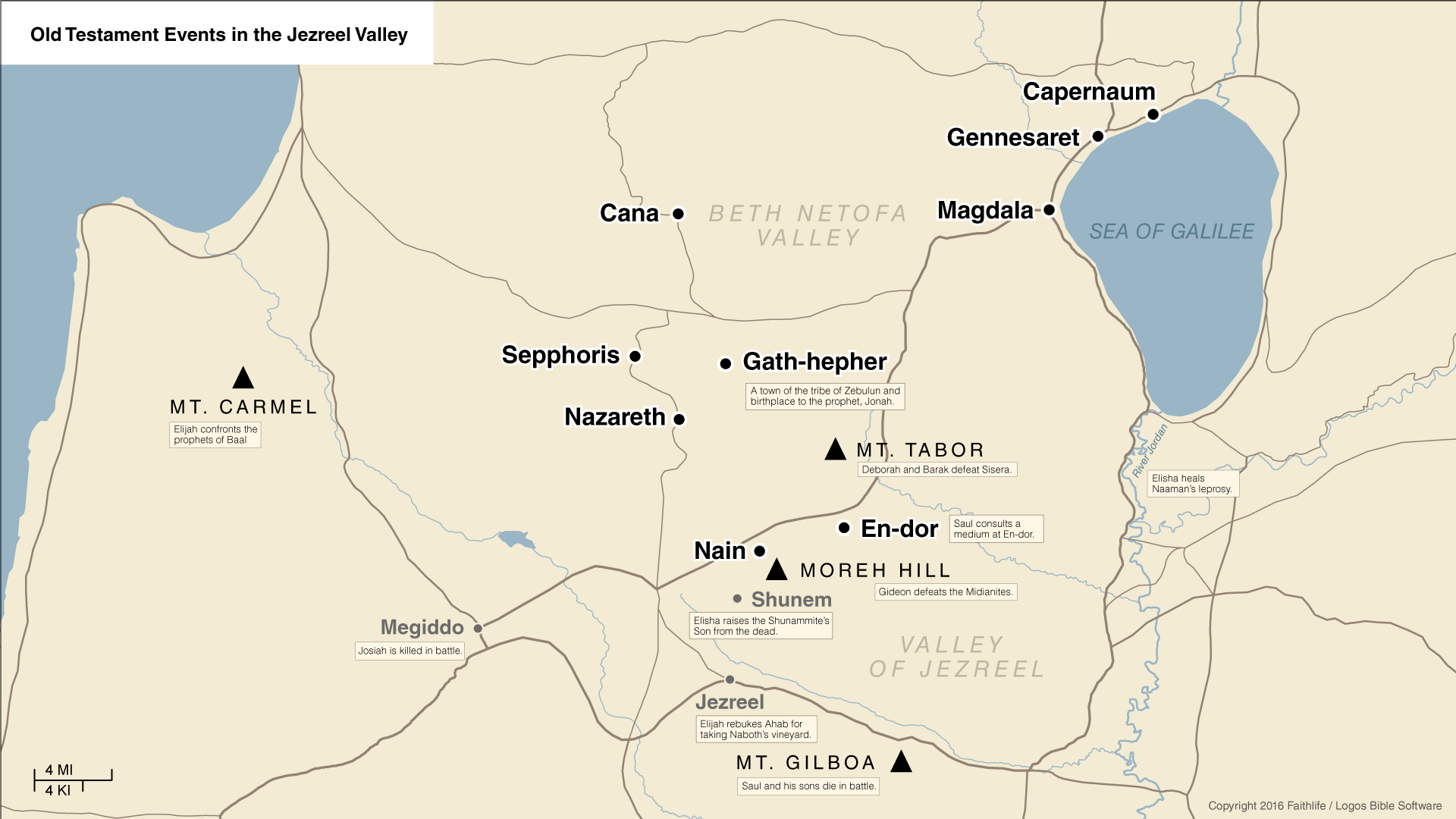

The below map shows where the Jezreel Valley is located and key events that occurred there in the Old Testament:

What strategic importance did the Jezreel Valley have?

Located at the crossroads of two international travel routes, the Jezreel Valley has always been of strategic importance for travel, trade, and military campaigns. The international highway passes through the valley, connecting the major centers of Egypt with Damascus. The coastal highway extends north from Egypt to Phoenicia. The great fortress city of Megiddo lies at the junction of these two highways.

There are six entrances and exits into the Valley of Jezreel:

1. From the south via the Dothan Pass. King Ahaziah was wounded near here (2 Kings 9:27–28). Jesus followed this route on His way to Galilee (John 4:39–44).

2. From the south via the Megiddo Pass. The inscription of Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III at Karnak reveals that he used this route when marching north to suppress a rebellion of Canaanite cities.2 Josiah tried to stop the Egyptian army led by Pharaoh Neco going north through this route (2 Kgs 23:28–30).

3. From the south via the Jokneam Pass

4. From the northwest via the coastal highway

5. From the northeast via the international highway

6. From the southeast via the Harod Valley. The Midianites used this approach when invading Israel during the period of the judges (Judges 6–8; also 2 Kings 9:14–16).

Historical geographer George Adam Smith provides the following description of the Jezreel Valley’s strategic nature, likening it to a stage:

With our eyes on these five [six] entrances, and remembering that they are not merely glens into neighboring provinces but passages to the sea and to the desert—gates on the great road between the empires of Euphrates and Nile, between the continents of Asia and Africa—we are ready for the arrival of those armies of all nations whose ceaseless contests have rendered this plain the classic battleground of Scripture. Was every arena so simple, so regulated for the spectacle of war? Esdraelon [Jezreel] is a vast theater, with its clearly-defined stage, with its proper exits and entrances.3

The Jezreel Valley, a “grand central station”

By Faithlife Staff

No one traveling north to south or east to west could avoid passing through the Jezreel Valley. It was the main connecting point between the nations, like a giant “X” in the middle of Israel—a grand central station of sorts.

And because it guarded the easiest route to the Fertile Crescent, whoever controlled the Jezreel Valley controlled travel and trade (ie., taxes).4

This flat valley and unique and strategic location—combined with two natural water sources—turned this land into the most contested piece of real estate in antiquity.

Perhaps this is why Napoleon called the Jezreel Valley the most natural battleground of the whole earth.5

***

What distinguishes the topography of the Jezreel Valley?

Three major mountains and one ridge distinguish the topography of the Jezreel Valley:

Mount Tabor

A 1,843-foot mountain located in the valley about 10 miles southwest of the Sea of Galilee. Several Old Testament poetic passages mention this mountain (Psa 89:12; Jer 46:18; Hos 5:1). Deborah and Barak’s troops attacked and routed the Canaanite troops under Sisera from Mount Tabor (Judg 4:6–14). Mount Tabor is traditionally regarded as the place of Christ’s transfiguration, though this is unlikely since the transfiguration took place in the vicinity of Caesarea Philippi on a “high mountain” (Matt 17:1).

The Hill of Moreh

The Hill of Moreh A 1,815-foot summit five miles southwest of Mount Tabor. It is mentioned in Judg 7:1 as the hill where Gideon attacked the Midianite camp. Christ raised the widow’s son in a village one mile north of the hill (Nain; see Luke 7:11–17).

Mount Gilboa

A mountain range 8 miles long and 3–5 miles wide, with a summit of 1,696 feet. Gideon camped at the springs of Harod (En-Harod) located at the foot of Gilboa before his attack on the Midianites (Judg 7:1). Saul and his sons died on Mount Gilboa (1 Sam 31). Ahab’s summer capital, Jezreel, was located on the western spur of Mount Gilboa (1 Kings 18:45).

Mount Carmel

A 2,000-foot mountain that extends to the northwest out into the Mediterranean Sea and forms the southwestern border of the Jezreel Valley. The mountain has three passes: Dothan Pass, Megiddo Pass, and Jokneam Pass. Elijah defeated the prophets of Baal at Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18).

See how the Logos Bible app can help you study the geography of the land of the Bible

What biblical cities are connected with the Jezreel Valley?

Beth-shean (Scythopolis)

Beth-shean (Scythopolis) is strategically located at the junction of the Jordan and Jezreel Valley. This city was able to command north-south and east-west travel routes through the region. The Egyptians recognized the importance of controlling this junction and built a palace/fortress at the site as early as 1500 bc. In spite of Joshua’s conquest of northern Israel, Beth-shean remained in Canaanite hands until the time of David (Judg 1:27, 17:9). It was here that the Philistines hung the bodies of Saul and Jonathan after their defeat at Gilboa (1 Sam 31; see Mazar, “Was King Saul Impaled on the Wall of Beth Shean?” 34–71). Thanks to David’s victories over the Philistines, Solomon was able to incorporate Beth-shean into one of his administrative districts (1 Kgs 4:12). In Roman times, the city was known as Scythopolis. It was one of the ten cities of the Decapolis and the only one of these Greek cities west of the Jordan.

The abundance of springs in this region provided water for a huge bathhouse built during the Roman period. The Romans also built a theater and an amphitheater there. Scythopolis was eventually destroyed by an earthquake in ad 749 and never returned to its original state of grandeur.

Megiddo

Megiddo is a 30-acre fortress that dates back to about 5,000 bc, located on the southwest side of the Jezreel Valley at the foot of Mount Carmel. The city commands entrance by a major pass—Nahal ‘Iron—through the Mount Carmel range. The strategic nature of the city is evidenced by the words of Thutmose III, “… for the capturing of Megiddo is the capturing of a thousand cities. Capture ye firmly, firmly.” (Pritchard. Ancient Near East, 180). Megiddo is mentioned among the cities conquered by Joshua (Josh 12:21). During the reign of Solomon, Megiddo was fortified along with Gezer and Hazor (1 Kgs 9:15). The city fell to Shishak (925 bc) and to Tiglath-pileser III in 733 bc. Josiah died at Megiddo in 609 bc in his confrontation with Pharaoh Neco (2 Kgs 23:29).

Archaeologists believe that most of what we see at Megiddo today dates from the time of King Ahab. Scholars debate whether the tripartite buildings discovered on the site were Solomon’s stables or storage rooms. When they were discovered at Megiddo, the presence of stone mangers led archaeologists to conclude that the buildings were stables for Solomon’s chariot force (1 Kgs 10:26). The discovery of nearly identical buildings at Beer-sheba with storage jars inside raised questions about the earlier conclusion. It seems best to conclude that buildings with the same architectural style could have been used for either stables or storage depending on the needs of the community.

Megiddo’s water system included a tunnel giving access to a spring outside the city walls. Not wanting the enemy to have access to Megiddo’s water source, builders buried the spring so the only access to the water supply was through the tunnel.

Jezreel

Jezreel is the city from which the valley takes its name. The city of Jezreel was located at the foot of Mount Gilboa on a rise overlooking the valley. To the west is Mount Carmel. To the south and east is Mount Gilboa. Directly east is the Harod Valley leading to the Jordan Valley, with the Hill of Moreh to the north. Ahab selected Jezreel as the location of his palace (1 Kgs 21:1). The palace overlooked Naboth’s vineyard, which Ahab coveted (1 Kgs 21:2–16). The main water source of the ancient city was a spring in the valley below the hill, so the inhabitants built cisterns into which rainwater was channeled to provide a more convenient and readily available source of water. King Saul camped at the spring of Jezreel the night before his last battle with the Philistines (1 Sam 29:1; see Ussishkin, “Where Jezebel Was Thrown to the Dogs,” 32–76).

Is the Jezreel Valley in prophecy?

Revelation 16:16 speaks of the kings of the earth gathering for an apocalyptic battle at Har-Magedon. Many have linked this reference with Megiddo and have identified the Jezreel Valley as the location of the battle of Armageddon. Kline argues that John’s reference has been misunderstood and Megiddo has been mistakenly identified as the location of this apocalyptic campaign. He suggests that Armageddon means “Mount or Place of Assembly” and refers to Jerusalem (Kline, “Har Magedon,” 207–22). Kline argues that if har means “hill,” Megiddo is not on a har, but a tel, and that John would know the difference between the two terms because he frequently makes allusions to places and events in the Hebrew Bible. Although he is writing in Greek, he is telling us that there is a Hebrew word behind this reference to “Armageddon.” If John had meant Megiddo, he would have written “tel.”

Kline further points out that the “g” sound in Hebrew can come from gimel or ayin. The name “Gaza” illustrates this. If the place name is spelled meym, ayin, dahlet, then the Hebrew word would mean “meeting place” or “place of assembly.” Biblical evidence suggests that armies will be gathering at Jerusalem in the last days for the final battle (Zech 12 and 14, Joel 3 and Isa 29:1–7). Jerusalem is worth fighting for, but not Megiddo, so John might be saying that the armies will gather there.

Will the final battle take place in the Jezreel Valley?

By Faithlife Staff

The Jezreel Valley tells a sobering story of past rulers and wars, but it’s a future battle mentioned in Revelation 16 that grabs many people’s attention.

In it the evil rulers of the world will gather to come against the King of kings—and the apostle John says it’s to a specific place:

For they are demonic spirits, performing signs, who go abroad to the kings of the whole world, to assemble them for battle on the great day of God the Almighty. . . . And they assembled them at the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon. (Revelation 16:14–16, emphasis added)

Though the entertainment industry has popularized the word “Armageddon,” it doesn’t refer to the end of the world. Its Greek name, Harmagedon (Ἁρμαγεδών, Harmagedōn) “appears to be a conflation of the Hebrew word for ‘mountain’ . . . and the name Megiddo (מגדו), yielding a translation like ‘mountain of Megiddo.’”6

Interestingly, back in 1903 archaeologists started excavating a “tel” in the Jezreel Valley (one ancient civilization built upon another) and identified it as the ancient Canaanite city of Megiddo, mentioned twelve times in the Old Testament.

Nations that controlled the Jezreel Valley controlled Megiddo; from there, they could keep a watchful eye on all traffic within the valley.

But was John referring to the city of Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley in Revelation 16:16?

Maybe.

Some interpreters hold that John, drawing on Megiddo’s reputation as a battleground, envisaged the whole plain of Megiddo in the greater Jezreel Valley as the site of the world’s final, epic battle.

Others argue “tel Megiddo” is not a mountain but merely a “tel,” or ancient city. And because the word “Armageddon” in Revelation refers to a mountain, John can’t be referring to the ancient city of Megiddo. Therefore, the Jezreel Valley is not the future gathering place of “the kings of the whole world” (Rev 16:14).7

Still others deny that either place could be the site. For example, Justin L. Kelly writes in the Lexham Bible Dictionary:

The idea that Megiddo or the Jezreel Valley should be the site of the world’s final battle is not in keeping with the eschatological outlook of the Hebrew Bible, in which Jerusalem is always the scene of the final battle between God and his enemies (compare Psa 48:1–8; Isa 24:21–23; 29:1–8; Joel 3:1–16; Mic 1:11–13; Zeph 3:8; Zech 12:1–9; 14:1–5).8

The author of the Revelation drew heavily on the eschatological imagery of the Hebrew Bible—especially from passages in Daniel, Ezekiel, and Zechariah (see Aune, The New Testament, 226–52; Collins, The Apocalyptic Imagination, 269–79; compare Gunkel, Creation and Chaos, 181–250). Thus, it would be surprising if the writer viewed the great battle as taking place at any other location than Jerusalem. Ultimately, this toponym is best understood in light of the Old Testament prophetic texts as a veiled reference to Jerusalem.

Finally, some believe “Mount Megiddo” in Revelation 16:16 is merely symbolic of the power of Rome to seduce nations.9

Regardless, John offers his vision of a final war on “the great day of the Lord Almighty” to persecuted Christians then—and to us now—as a word of comfort and hope that evil will never win but is doomed to ultimate destruction.10

And wherever that battle is, it will be the greatest showdown in history.

***

See how the Logos Bible app can help you deepen your study of more topics like the Jezreel Valley.

Related resources

Mobile Ed: TH341 Perspectives on Eschatology: Five Views on the Millennium (4 hour course)

Regular price: $149.99

Encountering the Holy Land: A Video Introduction to the History and Geography of the Bible

Regular price: $99.99

- Cline, Eric H. The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age, University of Michigan Press, 2002, p. 11

- (1468 bc; Aharoni and Avi-Yona, The Macmillan Bible Atlas, 32).

- Smith, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, 253

- Cline, Eric H. “Contested Peripheries” in World Systems Theory: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley as a Test Case,” p. 9, file:///Users/karen.engle/Downloads/233-318-1-PB.pdf. Accessed 2019 March 22.

- Rhodes, Ron. Bible Prophecy Answer Book, “The Campaign of Armageddon,” Harvest House Publishers, 2017.

- Barry, John D. Lexham Bible Dictionary, “Megiddo and ‘Armageddon,’” Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ewell, Walter A. Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, “Armageddon,” Baker Academic, 2001.

- Ibid.