I

Maybe you’d ask, “Why would I read C. S. Lewis’ writings from before he became a Christian?” It’s a question I’ve asked too, and here’s what convinced me:

- We cannot completely understand Lewis’ works without knowing his context. Like us, C. S. Lewis was a complex person. He didn’t write, read, or teach in a vacuum—no, the place, time, and community he was born into shaped him. We would not have gotten Lewis the apologist without first getting Lewis the atheist.

- We see the before-and-after difference Jesus makes. As Peter Leithart says in his endorsement of Spirits in Bondage, “This cycle of poems helps us pinpoint the difference conversion made to one of the world’s most celebrated converts.” It’s staggering to see the young Lewis in these poems grappling with matters that would one day mark his ministry. These night-and-day differences remind us to thank God for the gift of conversion and pray for people in our lives who are searching for answers.

- It reminds us that our heroes in the faith are human. C. S. Lewis wasn’t born a theologian. He didn’t have a straight shot to Christ and ministry—and even once he became a Christian, he still wasn’t a perfect Christian. Much as we respect him for works like Mere Christianity and The Chronicles of Narnia, he is also the man who wrote Spirits in Bondage. In a time when celebrity culture invites us to put leaders on pedestals, we would do better to see them as they really are—and realize they aren’t so unlike us.

Below, you can read one of Lewis’ poems from Spirits in Bondage, but before you do, two quick things:

1. If reading poetry feels uncomfortable or like a distraction, you may be overthinking it. Take a deep breath, then read the words out loud, noticing the rhythm, momentum, and unexpected words or phrases. Pause where the punctuation notes a pause (commas, semicolons, periods, etc.) instead of where the lines end. Give it a try.

2. You’ll need a little background on the poem’s setting. Karen Swallow Prior explains in the book’s introduction:

The second poem, “French Nocturne (Monchy-Le-Preux),” is among the best in the collection, painting in terse, economical language the existential horror of the front lines of World War I. Amid the setting of a “sacked village,” the “jaws” of which have “swallowed up the sun,” where a “buzzing plane” veers “straight into the moon,” despair culminates in the speaker’s realization that the young soldier, who is barely a man, becomes an animal: “I am a wolf.” He and his “fellow-brutes that once were men” only “bark for slaughter: cannot sing.” Like many of the poems, this one reflects what Lewis later explains in Surprised by Joy about this time of his life: “I was at this time living, like so many Atheists or Antitheists, in a whirl of contradictions. I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing. I was equally angry with Him for creating a world.”

***

FRENCH NOCTURNE

(MONCHY-LE-PREUX)

Long leagues on either hand the trenches spread

And all is still; now even this gross line

Drinks in the frosty silences divine,

The pale, green moon is riding overhead.

The jaws of a sacked village, stark and grim,

Out on the ridge have swallowed up the sun,

And in one angry streak his blood has run

To left and right along the horizon dim.

There comes a buzzing plane: and now, it seems

Flies straight into the moon. Lo! where he steers

Across the pallid globe and surely nears

In that white land some harbour of dear dreams!

False, mocking fancy! Once I too could dream,

Who now can only see with vulgar eye

That he’s no nearer to the moon than I

And she’s a stone that catches the sun’s beam.

What call have I to dream of anything?

I am a wolf. Back to the world again,

And speech of fellow-brutes that once were men

Our throats can bark for slaughter: cannot sing.

***

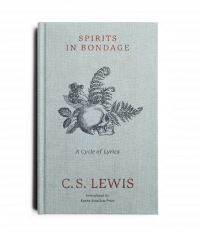

Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics is now available in a modern reprint from Lexham Press. With an award-winning cover and an illuminating introduction by Karen Swallow Prior, this is a book worth owning—in print and in Logos. Make it yours today.