Have you ever noticed that some Old Testament figures are given one name when they’re introduced and then referred to by a different name or expression as the story unfolds? Think of the various names and expressions used for God throughout the Old Testament. We know they’re used to highlight a particular aspect of God’s character, but did you know that the same thing happens with other biblical figures too?

Believe it or not, the biblical writers did this for the same kinds of reasons we do it! Here’s what I mean. As I returned home from work a few weeks ago, Bri greeted me with the following statement: “your daughter put the TV remote into the dishwasher and it got washed.” Notice she didn’t say, “Estelle put the TV remote . . .” or even “Our daughter put the TV remote . . .” She purposely phrased it this way. Why? Calling Estelle “your daughter” in this context conveyed a specific meaning: my wife’s innocence in Estelle’s action and my (genetic) culpability. The subtle but deliberate mode of reference was very meaningful. We see the same sort of thing happening in the Old Testament.

In 1 Samuel 9, we meet Saul, Israel’s first king. In all but a few places, he is referred to by his given name. Several times, however, the writer changes from Saul to king. Why? Changed reference devices most often highlight a particular quality of the person referred to. The highlighted feature forces us to change how we view that character in the particular context. This change results in a unique and specific meaning.

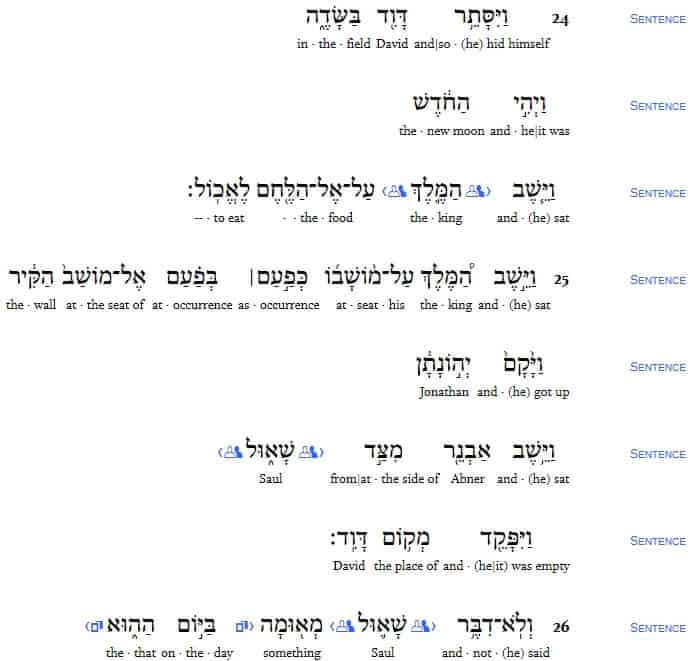

The Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible uses the symbol to mark each changed reference. Let’s take a closer look at how it’s used in 1 Samuel.

In 1 Samuel 20, David and Jonathan hatch a plan to find out just how intent Saul is on killing David. The plan involves Jonathan lying to Saul, informing him that David has chosen to go to Bethlehem rather than attend the feast of the new moon, where Saul expected David to be. If Saul becomes angry at the news of David’s absence, then David and Jonathan will know for sure that David’s life is in danger.

In the climactic scene recounted in 1 Sam 20:24, we read: “When the new moon came, the king was seated at the feast” (LEB). As Saul learns of the reason for David’s absence, he flies into a murderous rage vowing to put an end to David’s life. He’s so out of control that he even throws a spear at Jonathan, attempting to murder his own son!

Is this how a king is expected to act? No! Each time that Saul is referred to as king, we find him acting very, well, unkingly.

The use of king rather than Saul highlights Saul’s role as king just as the climactic scene begins. This forces us to view him in light of the character traits one expects God’s anointed king to have. But Saul’s behavior in this scene is anything but that of a righteous king. Referring to Saul as king in the context of unkingly behavior conveys a specific meaning: Saul’s unworthiness to serve as God’s anointed king.

When we look at each place in 1 Samuel that king is substituted for Saul, we find that this occurs only in parts of the story where Saul’s actions appear less than kingly! As you can see, these changed references are exegetically significant, but they’re easily overlooked or misunderstood.

The Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible and Lexham High Definition Old Testament help you to get the most out of your Bible study by annotating each changed reference, as well as 29 other exegetically significant discourse devices. We’ve included an introduction and glossary to help you understand the function of each device. The Lexham High Definition Old Testament is a terrific resource for those who haven’t studied Hebrew. It includes nearly all of the devices marked in the LDHB.

Get the Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible—or grab the 8-volume Lexham Discourse Bible, which features the Discourse Hebrew Bible and the Discourse Grammar of the Greek New Testament, plus a glossary and introduction resources